The Beautiful Mrs Graham:

The Cathcart Circle

By Maxtone Graham

This book is awesome! Truly. We read it in the hope of gleaning any information and comments about clothing but the ladies of the Cathcart Circle don't seem to be too obsessed with what dresses they wore. It was, however, an absolute goldmine in socially historical facts.

It is, essentially, a collection of family letters dating from the mid 18th century and with the author filling in the general background as the years progress. The letters come thick and fast and are just such an amazing read when you consider that most of them were simply written between 3 sisters. As a reader it would've been nice to know where the author gets the background information from - whether there was a diary also found with the letters or a family accounts but apart from that the letters pretty much lie in consecutive order and follow the story of 9 siblings.

It starts off with Lady Cathcart, the mother or these 9 and her ambassador-of-a-husband Lord Cathcart, during their time in Russia - which is awesome enough. Seeing a glimpse of Catherine the Great and her court is fascinating. The first scanned-in page here describes a social function that they were invited to, fairly early on in their appointment to Russia. It's incredible. Firstly, they're having a meal where the food arrives through the table, and what's more; they start having fun with it and asking for ridiculous things. Please read this glimpse of a real event in 1768 as it's kind of unbelievable.

Some of the main names in Catherine the Greats reign are mentioned on these pages and although every thing reads lovely and splendid there is an undercurrent hint of what was going on in Catherine's court. The author mentions that letters were possibly checked and that there was a great sense of spying in Catherine the Greats court that made being honest in letters less likely. We know none of this through the actual letters.

It also has a couple of letters that Lady Cathcart wrote to her daughters when she suspected she was dying. The author also includes in this section a letter that the 9th Lord Cathcart wrote to all Lady Cathcarts friends after her death and it starts with a quote from another letter she wrote. We are so tempted to steal this quote, it's as if it is from the very pages of Shakespeare and is pure beauty. She must've been quite a lady and quite a believer.

"Foolish Eyes! must you be swimming in tears because of those Things? Is not the Day of our Death as natural as that of our Birth?...I mix these very few tears with yours, dear kind fellow creatures; we shall meet again; I trust in happiness through the merits of a crucifed Saviour. Weep not long, but ever remember me with the Balm of Friendship."

These words take on specialness when your remember that this was a lady writing to her friends in real life and not a stage production.

The 9 siblings of Lord and Lady Cathcart are:

- Jane born 20th may 1754. Married 4th Duke of Atholl. Died 1790. Had 5 sons and 4 daughters.

- William, born 17th Sept 1755. 10th Lord and 1st earl Cathcart. Married Elizabeth Elliot. Died 16th Jun 1843. Had 6 sons and 4 daughters.

- Mary (our 'Beautiful Mrs Graham') Born 1st March 1757. Married Thomas Graham. Died 26th June 1792. Had no children.

- Louisa, born 1st July 1758. Married 7th Lord Stormont in 1776 and then Hon. Robert Greville in 1797. Died 1843. had 4 sons and 1 duaghter with Lord Stormont and 1 son and 2 daughters with Hom. Greville.

- Charles Allan, born 28th Dec 1759. Unmarried and died at sea 10th June 1788.

- John, born 23rd April 1761. Died at 10 months.

- Archibald Hamilton, bonr 25th July 1764. Married Frances Hanrietta. Died 1841. Had 1 son and 7 daughters.

- A son still born - 7th June 1768.

- Catherine Charlotte, 8th July 1770. Died Unmarried 20th Oct 1794.

- William, born 17th Sept 1755. 10th Lord and 1st earl Cathcart. Married Elizabeth Elliot. Died 16th Jun 1843. Had 6 sons and 4 daughters.

- Mary (our 'Beautiful Mrs Graham') Born 1st March 1757. Married Thomas Graham. Died 26th June 1792. Had no children.

- Louisa, born 1st July 1758. Married 7th Lord Stormont in 1776 and then Hon. Robert Greville in 1797. Died 1843. had 4 sons and 1 duaghter with Lord Stormont and 1 son and 2 daughters with Hom. Greville.

- Charles Allan, born 28th Dec 1759. Unmarried and died at sea 10th June 1788.

- John, born 23rd April 1761. Died at 10 months.

- Archibald Hamilton, bonr 25th July 1764. Married Frances Hanrietta. Died 1841. Had 1 son and 7 daughters.

- A son still born - 7th June 1768.

- Catherine Charlotte, 8th July 1770. Died Unmarried 20th Oct 1794.

The lives of these siblings cover glimpses into the English Court of George III, his wife and his illness. It includes the British politicians and some of the court life surrounding these notable figures. When the 3rd sister goes to France we see a window into the court of Marie Antionette and King Louis XVI. It has two brothers serve in the American Independant War, experience India, give accounts of being at sea and talk of the French Revolution. It contains letters from the Duchess of Devonshire, snippets from Robert Burns and other notable people. Each page kept me totally entranced.

It also stamped all over some of our ideas that we had built up from reading other books. Lisa Picard in her fabulous books - particularly Dr Johnson's London, suggests that' Supper' isn't a thing that happened in the 18th century. The main and only meal being 'Nooning' or 'lunch'. We've also researched this in other areas and the general idea is that this main midday feast began to become more fashionable at say 2:oo, then 5:00 and then 8:00 with the Victorians, which then opened up space for lunch to happen again. What's mentioned in these letters here doesn't always correlate with this idea. Can we just say; that we're not disagreeing with Lisa Picard, who we think is wonderful and who obviously came across this idea of nooning in contemporary historical documents. It's simply that it's not what we read in these pages. Firstly the word 'Supper' is used and secondly it is used in connection with an evening meal. Also, the balls had 'Suppers' included in them. This book also tramped all over our idea (again mostly from probably mis-understanding Lisa Picard) that Christmas wasn't an idea that was celebrated back in the 18th century; that it was Michaelmas that they celebrated and that it was a root of our version of Christmas. Again; this doesn't seem to tie in with these letters. Christmas is mentioned several times and one particular letter by Jane Cathcart (known only ever as the Duchess in these letters once she was married) describes guests having problems travelling to them through the snow. She also mentions some of the decorations. It also has bits that surprised me: they are willing to talk about cheapness - p.176-177, a wonderful moment where they get stopped in their coach by 'footpads', Lady Louisa Stormonts arranged marriage and her letters from the time - Talk about humilty! It's quite something to read someone going through the process of an arranaged marriage and see what she writes to her very close sisters - it's not at all what you'd think.

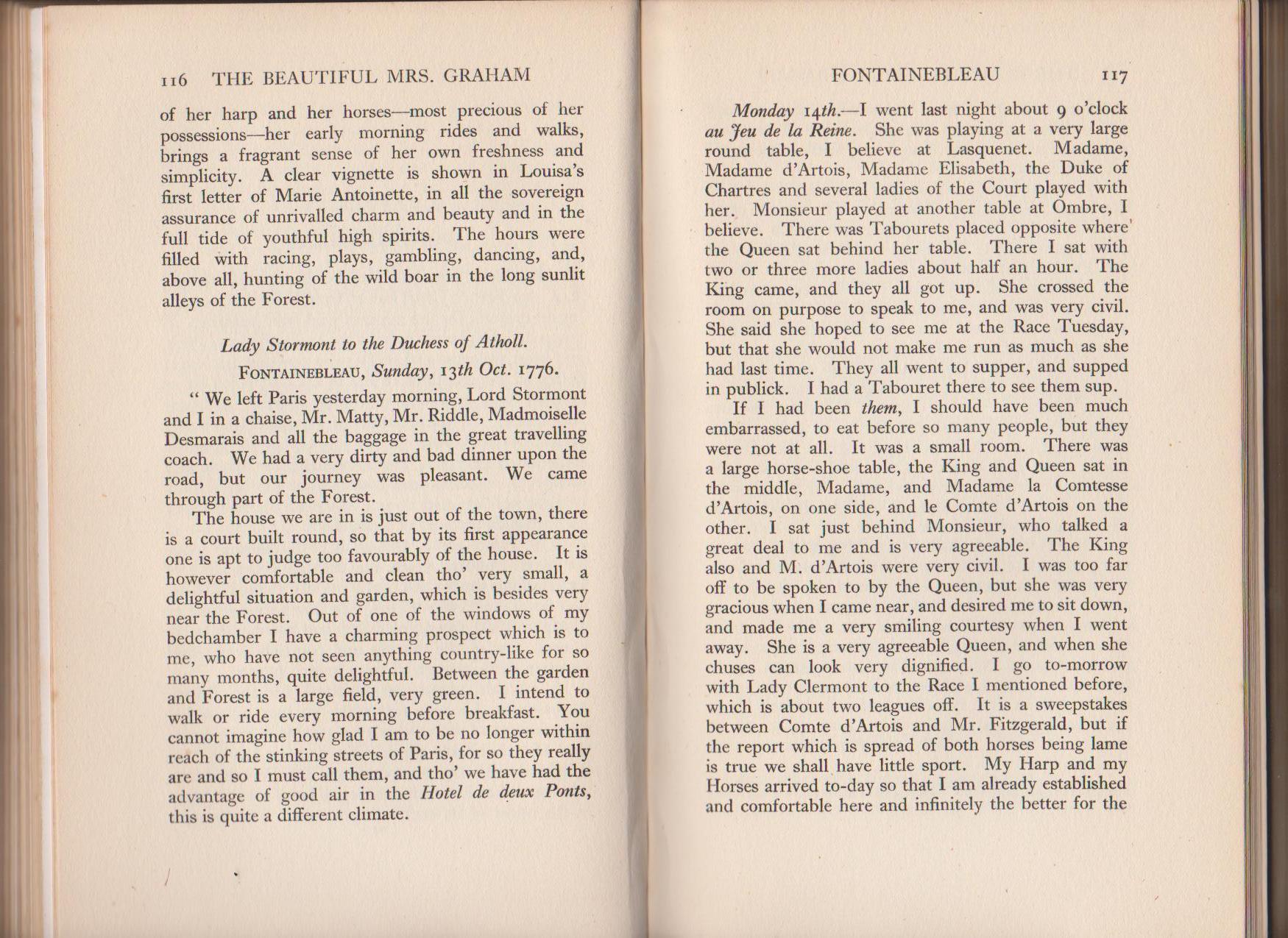

In the pages below is Lady Stormant's letter to her sister, the Duchess of Atholl, describing her first experiences of the French Court at Fontainebleau and the countryside retreat there.

Ann Buck in her book 'Dress in Eighteenth Century England' used quotes from various letters to show the difference between the English and French cultures and how the English Court's tradition of moving out of London and to the country was a horror to the French ladies. 'A French Lady told me she thought the English women not so happy as the French...' Mrs Montagu writes in 1776, 'I smiled and said I was not sure of that. She gave it as one reason that they were obliged to spend part of the year in the country. I combated her opinion, but found it impossible to make her comprehend the pleasure of a morning or evening walk...' (A.Buck, page 50). Therefore, I was quite surprised to read how the french court took leave of Versailles to go to a place in the country, hunt, race and take picnics. In the clip below you do not have all the letters that appertain to this Countryside retreat but you have Lady Stormont's first encounter of this place.

Ann Buck in her book 'Dress in Eighteenth Century England' used quotes from various letters to show the difference between the English and French cultures and how the English Court's tradition of moving out of London and to the country was a horror to the French ladies. 'A French Lady told me she thought the English women not so happy as the French...' Mrs Montagu writes in 1776, 'I smiled and said I was not sure of that. She gave it as one reason that they were obliged to spend part of the year in the country. I combated her opinion, but found it impossible to make her comprehend the pleasure of a morning or evening walk...' (A.Buck, page 50). Therefore, I was quite surprised to read how the french court took leave of Versailles to go to a place in the country, hunt, race and take picnics. In the clip below you do not have all the letters that appertain to this Countryside retreat but you have Lady Stormont's first encounter of this place.

Lady Stormant, the 3rd youngest sister and who spent a lot of time in Paris as an Ambassador's wife, writes often about French fashions and what her sisters should wear if they came over. She writes in one letter in the prospect of Mary Graham (a.k.a The Beautiful Mrs Graham) visiting 'If you have a new black (they were in mourning at the time) silk sacque, very handsome, bring it, if not don't for hoops and everything are different here from what we wear...I am trying to recollect your gowns. I think you have a pretty spring silk which was in a court dress and a trimming, which would make a very handsome sacque." I've highlighted this quote as it creates an interesting idea that though Lords and Ladies, their dresses weren't necessarily worn and discarded in the same manner as we picture and in the same manner as we do today. Perhaps it's easy to assume a snobbery in dress about re-wearing items or always having to have dresses new for all of the Nobility and the fashionable but this quote, atleast hints to that not necessarily being the case.

The Duchess of Atholl ( Mrs Graham's older sister) was a high figure in society. William the older brother, married an American lady, Elizabeth Elliot, known as Lady Cathcart in the letters. Lady Cathcart became very closed to the queen and when Small Pox broke out near where they lived, Queen Charlotte took her aside at Court and virtually demanded that they took possesion of Frogmore House to escape the illness. Her roles in court were Governess and Lady of the Bedchamber in 1795 to the Queen and Lady-in-Waiting in 1801 and 'finally Mistress of the Robes'.

Catherine Cathcart, a younger sister of Mary, Louisa and Jane, also became 'Maid of Honour' to Queen Charlotte who was her Godmother.

Quotes from the Letters about Fashion:

- p.53: "We dined today at Coventry, where we bought ribbons, some of which I send you; I don't know whether you will think them very pretty, but it was the manufacture of the place and the newest they had. You will want variety at the Races and they may happen to suit some of your gowns. "

- P.54: "I will also endeavour to send you a pair of Riding Gloves, which are made of fawn skin; we got them at Woodstock, where they are famous for making them." ( These two quotes are especially interesting to us after reading Dress in 18th Century England by A.Buck as she mentions quite deeply the various places of trade in the U.K)

- P.69: "My Habit is pretty, something like yours in colour with little buttons like those on Graham's green riding-dress, in the last fashion."

- P.69: " Mr Greville has given me abundance of charming and very long feathers from Paris, but I hvae not yet that the courage to wear the longest of them, for Papa is generally in the carriage and I cannot sit down without removing the cushion, which would not please him."

- "Lady B. has given me a dress for my birthday of blue satin which must be trimmed. Mixed colours are all the fashion. Puce and couleur des cheveaux de la Reine are the most fashionable."

- P.74-75: "Everybody was in mourning and a great many in white polonaises. Miss D. Wrottesley I suppose not being provided with one, thought black would do as well. It was one of those that are loose behind (we are intrigued by what this means!) and was tied up with two little knots of white ribbon, which had a very singular effect; it was laced with narrow white ribbon which with her dancing amde her a most visible figure."

- P.82: QUOTE OF THE MONTH! "He told me I should never appear at Paris without rouge."

There were many more quotes and wonderful information within this book but we shall leave that pleasure to you, to be able to dig inside this book and find each page a total surprise as we did!

A List of Portraits that we could find of some of the People mentioned in this book!

- Comtesse D'Artios. She is mentioned fairly frequently in Lady Stormont's letters as a close friend to Antionette. There is only one bit where Louisa comments on her character and it's when she first meets her and says: "I went to Madame with the same ceremonies, Monsieur also coming in, they are both very agreeable, then I went to Madame d'Artois, who is not so much so. Mons. d'Artois was a little embarrassed, and she not a little." Whenever Lady Stormont mentions her again it is literally to say she was there and what she was doing, there appears to be no other description of her character.

- Obviously Marie Antionette is mentioned very often and Lady Stormont says some very nice things about her. "The Queen was very talkative and agreeable though she was frightened too. She is a most agreeable figure, I think something like Lady Granby, and is vastly pleasing. The king came in, as soon as they had been to tell him. We all got up and he talked to me a little while and then went away. We sat down as before for a moment, then the Queen got up and we made our exit with three curtesies backwards, kicking away the bas de robes with one foot, as the Actresses do, which is absolutely necessary so as not to fall."

- The King doesn't get many mentions, its all pretty much the same as the above text. Here's another account of her experience at court where, again Lady Stormont gets to sit on a Tabouret which apparantly was a great honour and they watched the King and Queen and the Comte and Comtesse d'Artios eat. It is also another example of supper in the evening, being after 9 at night. "They all went to supper, and supped in publick. I had a Tabouret there to see them sup. If I had been them, I should have been embarassed to eat before so many people, but they were not at all. It was a small room. there was a large horse-shoe table, the King and Queen sat in the middle, Madame, and Madame la Comtesse d'Artois on one side and le Comte d'Artois on the other. I sat just behind Monsieur, who talked a great deal with me and is very agreeable. The King also and M.d'Artois were very civil. I was too far off to be spoken to by the Queen, but she was very gracious when I came near, and desired me to sit down, and made me a very smiling courtesy when I went away. She is a very agreeable Queen and when she chuses can look very dignified."

- Madame d'Epinay is also mentioned in Lady Stormont's letters to her sister Mary. Having described meeting some of the Original Salonieres, such as Madame de la Tallien and Madame du Deffand, she now decribed going that same evening to see Madame d'Epinay "who is a great favourite of Lord Stormonts and in the same stile as those I have mentioned. She has some illness that confines her entirely, and the physicians have told her she can never expect to go out of her house again. She is between 40 and 50, looks much younger and rather pretty." This portrait here was painted 17 years earlier than the quote given above that was written in 1776 from Paris.

- David Garrick is another celebrity mentioned on these pages. Described in the Duchess of Devonshire's letter to Mary Graham she says: "Mr Garrick is just going to read to us two Acts of Macbeth; I have just got a little moment before he begins to write to you in. " She follows this statement later in the letter with: "I do assure you I have no terms to express the horror of Mr Garrick reading Macbeth. I have not recovered it yet. It is the finest and most dreadful thing I ever saw or heard, for his action and countenance is as expressive and terrible as his voice. It froze my blood, as I heard him and I have scarcely got rid of the dreadful idea yet. My sister's nerves were very much shaken by it. She has been nervous and low all to-day."

- Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire by Gainsborough - have yet to find a date.

- As mentioned above there is also a few mentions of the infamous Duchess of Devonshire. but in the two letter extracts mentioned in the book, she sounds quite genuine and, as they would say back then: agreeable. Charles, the younger brother writes here "I have seen the Dutchess of Devonshire, she looks vastly well. All that party wear Fox ribbands and laurels. The prints have amde infamous caricatures of her." With his own political life in full swing, he writes in 1784 of not wanting to be 'intimate with people I have named' as it "would put me in their power more that I wish. I hope I have not offended the Duchess of Devonshire by not going to any political meetings there; if I have, I will plainly tell her my reasons."

Before Mary Graham died, she was visited by Mrs Nugent who wrote a letter describing the conversation they had had. Here Mrs Graham also mentions the Duchess of Devonshire, and I quote (remember this is Mrs Nugent writing) "She resumed the conversation giving the greatest character of the Duchess of Devonshire, 'clever, safe, benevolent'. Then 'Tell her to thank Lady Spencer for all her kindness to me."

- Madame Necker is another that is often mentioned in the French Society, where her and her husband were part of the Diplomatic circles. Although described as a little boring by Mdm du Deffand they were still obviously a close part of society there in Paris. Lady Stormont writes in 1776 "I supped at St Ouen Saturday; this place belongs to Monsieur and Madame Necker whom the Duchess (Jane Cathcart, the older sister) knows. They are a good sort of people and very civil to us. Madame is a sensible woman, reckoned very clever, in short what is generally called a Bel Esprit, that talks of the Voltaires and Rousseaus, and disputes on this and t'other subject. However, I must say in that stile she is very agreeable, for she does not always talk fine."

- William Pitt the Younger. Charles, when not off with the Armed Forces, began to shape for himself a political career. It is in his letters that the most in-depth perception of the British Parliament are painted. We know from what the author writes as part of his background that William Pitt appointed him to go to China to open intercourse with that nation. He writes in 1787 "I am very sorry that it is impossible for me to come down to Scotland. You write to me plump about China. I have been instructed not to mention where I am going, but in conversing with you we will suppose that I am going to China - a supposition which should my particular friends put to me I would disavow...". There is also the political side, and Mr Pitts' involvement, in the illness of George III and the Regent's accession into power. Lady Stormont writes in 1788 to Mrs Graham that "Mr Pitt is soliciting addresses to the Regent from all the towns in England to keep him in power. Pray mention without quoting me, that 'you will soon see address for Mr Pitt's continuing Minister, as the letters to that purpose are writing with all Expedition. I fear my brother is too much influenced by living with those people, he does not feel this, but I am sure it is so. There is not the least amendment (in the Kings mental condition) or appearance of it, but it is treason in any person to speak the truth. Dr. Willis, a determined Pittite, is not deceived himself, but he assists Mr Pitt in the deception of the rest of the world."